In November 2021 the Community Liver Alliance (CLA) and the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (NVHR) held a summit that brought together medical and public health providers, policy makers, advocates, and people with lived experiences to talk about Hepatitis C elimination among people who use drugs (PWUD) in Appalachia.

Suzanna Masartis is the CEO of the Community Liver Alliance and Daniel Raymond is the Director of Policy at NVHR.

Q: Your summit report mentions the overlapping epidemics of Hepatitis C and substance use—especially opioids—in Appalachia. Why are these issues so prevalent in Appalachia compared to many other parts of the U.S.?

Daniel: That is a complex question. The way that I think about it is as a combination of availability and vulnerability. We have seen in the news over the last few years a lot of discussion of lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors, and pharmacies. While a lot of the headlines today in the region are dominated by talk of fentanyl-related overdoses, before fentanyl there was heroin. And before heroin, there were prescription opioids. That was really where the roots of the problem seemed to stem. There have been lots of examples. For example, drug stores in West Virginia were receiving hundreds of thousands of these prescription opioids, far more than a small community could plausibly need for medical purposes.

We also see in terms of vulnerability that the initial patterns of non-medical use of prescription opioids were intertwined with a lot of different factors. For example, people whose livelihoods required physical labor. People like coal miners or furniture manufacturers often initially became exposed to prescription opioids due to chronic pain, lower back pain, or physical injury related to their jobs.

In a broader macroeconomic sense, the economy in Appalachia has shifted dramatically over the last few decades, with a lot of erosion of the job base in different sectors. Part of what we see around the country is that better-paying jobs were moving towards more urban areas with higher concentrations of people with college educations. Whereas places with a lot of rural areas, which include a lot of Appalachia, were often left behind in the broader economy. We found more people getting jobs in tech sectors, for example, that were not based in the region.

Clearly, there are multiple factors at work, with the spark being the influx of the availability of unchecked prescription opioids, driven by a number of factors—we could include greed amongst them, certainly. And the kindling was the social and economic conditions that made people vulnerable to something, whereas there might have been other places with more resources and more community resilience to mitigate that path.

In planning the summit, I’m proud to say that we took a broad view that addressed these diverse factors. We invited social scientists, like Lesly-Marie Buer, who spoke to many of the socio-economic factors that impact the health of PWUD. I encourage everyone to check out her presentation.

Suzanna: I would say that we also have to consider the multi-generational addiction aspect: children growing up around family members with substance use disorders that dovetail with all the reasons that Daniel just spelled out. We also intersect that with the lack of an adequate number of licensed treatment facilities, and then layer stigma on top of that. It’s a multifaceted problem but something that is necessary to tackle and that was our aim through this summit. Our hope was to bring a myriad of people together to talk about this, particularly people with lived experience.

Q: That brings me right to my next question, which is that the summit made a point to include those with lived experiences with the Hepatitis C epidemic in the conversation. Why is it so important to have these individual perspectives, and what did they have to say?

Daniel: This is a value that Suzanna and I share in both of our organizations. We focus on making sure that the voices of patients and people with lived experience are at the center of any discussions of Hepatitis C policy, programs, and planning. What we have learned from that is what the real needs and challenges are, what the assets of the populations in need or at risk are, and how their preferred ways of accessing care, accessing support, and accessing services can best be delivered.

Somebody I was talking to recently, outside of the region, said that when she was on a project that started a syringe services program, they had to make a lot of adjustments as they learned that the things that they were offering differed from the things that the population of people who use drugs (PWUD) in that community were actually looking for. It was when they started to listen, take on input, and solicit feedback that they really got a better idea of how to make their program effective. I think those voices, not just from an implementation standpoint, but in terms of things like values and honoring the dignity and respecting the capabilities of people who use drugs (PWUD), have been central to our planning and to the summit.

Suzanna: Sharing that lived experience of healing, wellness, and encouragement for others is important too. We feel that people with lived experience have a lot to offer, and the grace that we can show each other and learn from each other will help to level the playing field to address this issue in a much more productive way.

Q: A common thread throughout your conversations about Hepatitis C in Appalachia is the role that fear and stigma around drug use play as a major obstacle to effective harm reduction and Hepatitis C treatment. What can advocates and policy makers do to reduce this stigma?

Suzanna: A comprehensive and coordinated communication strategy is important to disrupt these negative attitudes and beliefs. They are ingrained in many of us, and these biases are shared not only by healthcare workers, but also across the board. Addiction is a chronic disease. I think that being able to craft these messages, particularly through work in viral hepatitis elimination, cannot be achieved without making people understand first that addiction is not a moral failure. Substance use disorders occur in all walks of life and persons with drug addictions don’t choose to live this life.

I remember when I first got involved in this work through the intersection of viral hepatitis and the opioid epidemic. Somebody said to me at one of our conferences that we were holding in Pennsylvania, “I didn’t know I was an addict until I did that one thing that I became addicted to.” And it was a light bulb going off over my head that really made me think, pause, want to learn more, and share because talking about it is the most important first step.

Daniel: One theme that came out in the summit was around stigma or bias encountered in the healthcare system. There are a lot of opportunities to work with clinics, healthcare providers, hospitals, and other sites where people are receiving care to start to break down those walls. There’s an opportunity to have real conversations, to provide some training and education, to make some real commitments that will make people feel more comfortable accessing care in those settings. Some of this stigma is a result of misunderstanding. A lot of it is that healthcare providers historically have gotten very little training on substance use disorder during their professional education. Some of it just has to happen through face-to-face conversations. We need opportunities for healthcare providers to hear directly from people who currently or formerly use drugs about what those experiences felt like on the other side of the exam table and think about how to reframe their approach through an anti-stigma lens.

Q: Several of the Summit recommendations focused on harm reduction. While we understand the overall importance of harm reduction as a component of comprehensive care for PWUD, can you elaborate on its role in promoting Hepatitis C elimination?

Daniel: While we’ve seen some improvements in other aspects of viral hepatitis elimination; the much better treatments than 10 years ago, the adoption of universal Hepatitis C screening; one of the areas that has lagged was harm reduction. More specifically, the prevention of new infections or reinfections amongst people who use drugs (PWUD). It was an area that many parts of the country have struggled with and that has often been politicized, but the evidence is clear that syringe services programs are an essential part of a comprehensive Hepatitis C prevention strategy. We wanted to make sure that as regions worked to build out their viral hepatitis elimination plans and build out their testing and treatment models that we could provide space for a meaningful conversation about harm reduction as the essential foundation to the success that they’re all hoping to see in eliminating viral hepatitis in their states.

Suzanna: You cannot achieve viral hepatitis elimination without harm reduction. It’s all of our concern to educate people more about this topic. Harm reduction is more than just needle exchanges. Harm reduction is multi-layered, and when you think about Appalachia being among the most affected by this—the new numbers show a 300% rise in infection rates—harm reduction strategies are vital to help reduce Hepatitis C transmission. Harm reduction is public health and we have to support the health of those who use drugs in underserved communities to help end transmission. Eliminating hepatitis C in Appalachia depends on successfully reaching the population of persons who use drugs.

Q: Your panel on ensuring adequate systems of care for PWUD in Appalachia mentions that, in addition to stigma, many state Medicaid policies are a barrier to Hepatitis C care. Can you speak more about what changes are needed to ensure adequate Hepatitis C care?

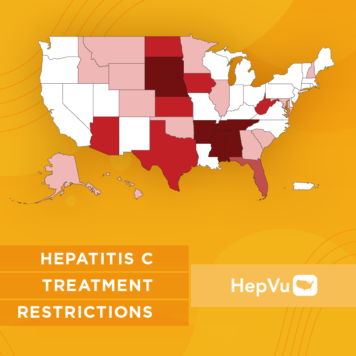

Daniel: NVHR is in partnership with the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI) at Harvard Law School on a project called the State of Hep C. HepVu has graciously covered that work previously. Through that project we have been tracking medically unjustified restrictions in Medicaid policies at the state level for authorizing prescriptions of Hepatitis C treatment. While we’ve seen some progress, we see several states continue to require that providers who wish to prescribe Hepatitis C treatment to their patients screen them for substance use first. In many cases that screening will require some form of counseling about treatment, or even mandate a period of abstinence or sobriety of three to six months. That requirement has been a significant deterrent to embracing the mandate to cure HCV in people with substance use disorders. It also reinforces stigma in the patient-provider relationship. It makes people afraid to seek care, and afraid to disclose their substance use. The data shows there is no medical justification for this, and that even people actively using substances can achieve very good outcomes on Hepatitis C treatment.

Another notable topic of conversation at the summit was about specialist requirements, which stipulate that Hepatitis C medications only be prescribed by a specialist such as a gastroenterologist or an infectious disease physician. That really goes against the trend. These treatments can be appropriately prescribed and managed in all kinds of practice settings, including primary care and community health centers. When trying to reach the most vulnerable patients where they are seeking care, a specialist requirement is often a burden that requires a referral or even traveling to an academic medical center. There are specialist shortages in many parts of the region. We want to work with stakeholders to update these Medicaid access policies and remove the unnecessary barriers that create undue obstacles and place undue burdens both on people seeking care and the providers that are aiming to treat them.

Q: What other measures did the summit recommend to advance the elimination of Hepatitis C among PWUD in Appalachia?

Suzanna: One that really rose to the top for me is building broad-based coalitions to advocate and build support for increased services—medical, behavioral, and social—to combat stigma, to advocate for more services, and to integrate Hepatitis C testing and treatment into harm reduction services. We are stronger together. When we can come together, and we all do our part we can affect real change.

Daniel: We will see progress when we see the engagement of diverse networks of stakeholders that include and make space for patients, people who use drugs (PWUD) and people with lived experience as active and valued partners. That is going to be essential moving forward.

We also wanted to frame the summit to make the case for tighter integration of Hepatitis C strategies into the broader responses to the overdose crisis in the region. We see a number of opportunities to collaborate rather than tackling these as two separate and unrelated problems. Can we weave those two things together? Can’t we use data on overdoses to inform our targeting of Hepatitis C prevention? Can’t we cross-train people working on overdoses and Hepatitis C? Can’t we start to build out more opportunities to integrate education and testing into programs that are working on the substance use treatment side, the recovery side, the harm reduction side, and all aspects of the spectrum? Something that we would be thrilled to see unfold over the next few years is a more integrated approach to this syndemic of overdose and Hepatitis C.