Rita Isabel Lechuga, MD, MPH, is a public health professional merging medicine and epidemiology as a Senior Manager on the Hepatitis team with NASTAD, overseeing the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Division of Viral Hepatitis (DVH) funded online technical assistance platform, HepTAC.

Your work has focused on infectious diseases like HIV and viral hepatitis in the United States and Latin America. What led you to pursue this line of research?

My interest in infectious diseases started in medical school. I am both Mexican and American and have lived my whole life with one foot in the U.S. and one foot in Mexico. As part of the medical education in Mexico there is a required year of “social service.” Before receiving licensure, one needs to provide clinical and epidemiological work in a community that is more rural, or that has fewer healthcare providers per capita. I decided to go to this little town in the Mayan Riviera, where yellow fever and dengue are endemic. It was validating for me to see how simple public health interventions such as vector control and community led waste management and clean-up campaigns had such a tremendous impact, which led me to go into more of a public health and epidemiology role. From there I was recruited by the World Health Organization (WHO) to work on HIV and viral hepatitis. Since then, it has been really motivating to me to see recent biomedical advances: Hepatitis C is now curable and there are vaccines to prevent Hepatitis A and B. Our commitment to eliminate viral hepatitis by 2030 now seems very reachable.

As part of that intersection of being both Mexican and American, I have also experienced difficulties navigating both healthcare systems. I believe that while we can put resources into eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030, this also requires us to address deeper systemic issues. My desire to address these issues continues to draw me into this space.

You currently oversee NASTAD’s HepTAC online technical assistance platform. What does HepTAC do, and how did this program get started?

HepTAC is an extension of NASTAD’s online technical assistance platform that was first created to address HIV through a cooperative agreement with CDC, and it is a program that really speaks to the history of NASTAD. We are a membership organization representing health department directors who oversee HIV and viral hepatitis programs and who, as a collective, decided to share and validate their unique experiences.

HepTAC is an extension of this idea in that we recognized a need for peer-to-peer networking as these public health professionals implement their viral hepatitis activities and as increased funding from the federal government allows for more staff to be hired. HepTAC helps support both prevention and surveillance activities at the health department level, but it is also a space for peer-to-peer knowledge exchange. What I do is facilitate these exchanges so that folks can not only learn from each other but can also validate each other’s experiences, such as navigating health department bureaucracies or strategizing about how to combat viral hepatitis with limited resources. This program got started through a cooperative agreement with the CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis in 2019, and we are now in the fourth year.

It has been especially exciting that the Division of Viral Hepatitis released a concurrent integrated prevention and surveillance grant for health departments. We are also invested in the success of this grant. Part of the work we are doing at NASTAD is to help jurisdictions build out these programs. A lot of this effort is providing best practices and providing a space for folks to feel listened to. NASTAD can also leverage all these needs internally, so if we hear folks need more funding for surveillance, we can then take this up and support with advocacy.

As noted by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, Hispanic people were 40% more likely to die from Hepatitis C than non-Hispanic white people in 2018. How should this disparity inform the public health response?

I think about this disparity in terms of how, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more widely known that such inequities exist. My concern here is while there’s an increased commitment from public health systems to address these disparities, we still need to look upstream for their causes. This not only needs to be informed by data but also needs to acknowledge that these inequities result from racism—racism that informs public policy.

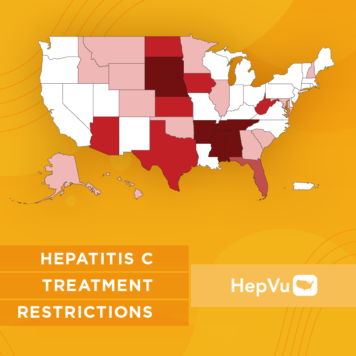

There are actual policies in place that are leading to these inequities. Issues like mass incarceration came from these very antiquated, racist policies that are still leading to these outcomes. This means applying an abolitionist lens because folks that are incarcerated are being exposed to viral hepatitis and yet are denied treatment and screening. That is a massive public health failure, and it is important that we make sure we place the onus on these systems and these policies that we are upholding.

What can the healthcare system do to better serve Hispanic/Latinx communities, especially with viral hepatitis?

It is easy in public health to narrow it down to stigma and to discrimination, when it is really the structural factors that are driving these inequities. Continuing to move upstream to address the root causes of health disparities is the only way for us to better serve Hispanic and Latinx communities. If we do not address what’s going on at the U.S./Mexico border, if we do not address the many barriers faced by Black, Indigenous, and people of color as they seek needed health and social services, it will not be possible to eliminate viral hepatitis.

With National Hispanic Hepatitis Awareness Day (NHHAD) and Hepatitis Awareness Month on the horizon, what is the main message you’d like to share with the Hispanic/Latinx community and viral hepatitis advocates?

I would start by validating the experiences that the Hispanic, Latinx, and Latine community face. Even being on the other end providing clinical services, I continue to find it so cumbersome and so expensive to navigate the healthcare system.

Another piece is also making sure that there is better public awareness about viral hepatitis. There was no other place in my life where I would have learned about viral hepatitis if it were not for my medical education. To me, considering there is a curative treatment for Hepatitis C, and a vaccine for Hepatitis A and B, the failure to eradicate viral hepatitis is down to systemic failures. The people that are sharing the brunt are BIPOC folks—including our Hispanic/Latinx community. I can validate those experiences, but we also need to empower folks and make sure that they know that it is not their fault they have viral hepatitis. It is really a failure of public health—if they cannot access services, if treatment isn’t available to them, if screening isn’t available to them, then the outcome is not on them. That is the core message I would like to share.