Evelyn M. Foust, MPH, CPM, leads the Communicable Disease Branch in the North Carolina Division of Public Health at the Department of Health and Human Services. Heidi Swygard, MD, MPH, is a Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Hepatitis C is a serious public health threat. An estimated 2.4 million people born between 1945 and 1965 are chronically infected with the virus, and acute Hepatitis C cases fueled by the opioid epidemic are now adding to the epidemic as most will not clear the infection. Inflammation caused by Hepatitis C is cumulative, and the scar tissue (fibrosis) can lead to cirrhosis; a subset of these patients will subsequently develop life-threatening liver cancer and decompensated cirrhosis. Liver cancer rates have tripled in the U.S. since 1980. Earlier treatments for HCV were fraught with side effects, prolonged treatment duration, and low cure rates. Newer antivirals have changed all of that, and cure is possible in the vast majority of cases.

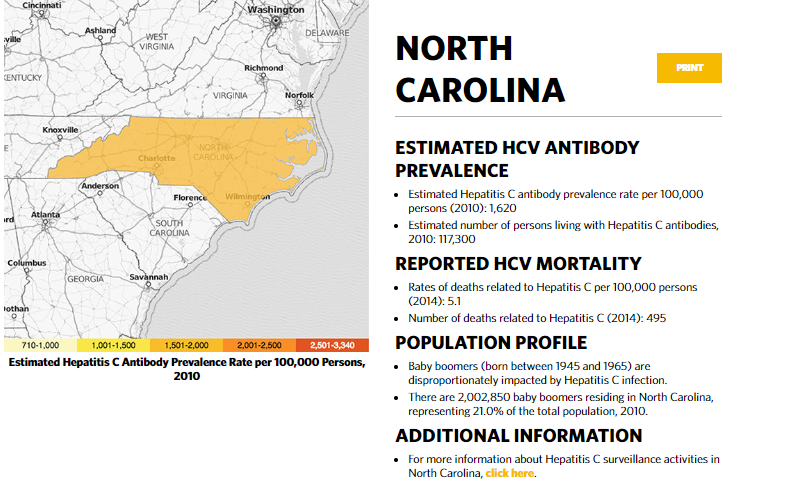

In North Carolina alone, an estimated 110,000 people are living with chronic Hepatitis C. Between 2010 and 2014, North Carolina experienced a threefold increase in the number of acute Hepatitis C infections reported, associated with the twin epidemic of injection drug use.

To help inform our response, the North Carolina Division of Public Health staff convened providers across the state to better understand their concerns about treating patients with Hepatitis C and conducted regional meetings in highly impacted areas to talk about barriers to screening, treatment, and care. Among the concerns voiced by stakeholders was a lack of access to care for underinsured and uninsured patients (e.g., resources for screening, diagnosis, and treatment), lack of administrative support, lack of training and expertise, limited mental health and substance abuse infrastructure, and care coordination. Providers noted that stigma often prevented people who inject drugs (PWID) from accessing care if it did not include harm reduction principles and services.

Based on this feedback, we developed the NC TLC (North Carolina Test, Link, Cure) program. NC TLC is designed to provide strategies to increase testing and early diagnosis among high-risk populations, expand educational messaging about liver health, and improve linkage to care and treatment, including for substance abuse and mental health services.

As a part of the TLC program, the Health Department worked in partnership with the UNC School of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, and academic leaders in Hepatitis C care to address the capacity to provide access to curative Hepatitis C care. Together we developed CHAMP, the Carolina Hepatitis Academic Mentorship Program.

CHAMP is designed to increase the number of primary care providers who can diagnose, care for, and cure persons infected with Hepatitis C. The program is based on a project ECHO model that increases access to specialty care beyond urban settings by linking primary care providers in remote locations to academic mentors for disease-specific training.

Clinicians begin the CHAMP process with an intensive, in-person “boot camp” with specific Hepatitis C content, followed by subsequent teleconference meetings in small groups twice monthly where providers can present cases to peers and academic mentors for review and feedback. Academic mentors are also available for additional consultations to manage more advanced or complex situations, establishing strong referral networks for patients with advanced liver disease.

Since October 2016, we have hosted three “boot camps,” including two in rural western North Carolina and have trained over 40 providers. In its first 12 months, CHAMP providers screened 7,500 patients and linked nearly 350 patients to care. Of those patients, 112 achieved a cure. In the fall of 2017, an additional 15 providers were enrolled (patient outcomes data currently in collection). This year we are planning a fourth “boot camp” for eastern North Carolina, and we will be planning additional offerings across the state in the future.

Hepatitis C is overlaid by complex social factors, which require a multipronged approach. In response, North Carolina built new partnerships and leveraged existing relationships with public health, medicine, and social services to achieve our elimination efforts and make a difference in the lives of people infected with Hepatitis C.

Acknowledgment: Special thanks to Drs. Michael Fried and Jama Darling (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Dr. Andrew Muir (Duke University Medical Center), Dr. Richard Moore (Rural Health Group) and Jane Giang, PharmD (University of North Carolina) for their help and support with this collaboration.