Suzanne Davies is a Clinical Fellow at Harvard Law School’s Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI).

Can you explain for our readers what a Managed Care Organization (MCO) is?

In the context of Medicaid, a Managed Care Organization (MCO) is a private entity that helps administer benefits to people who are enrolled in the state Medicaid plan, essentially a payment model for healthcare delivery. When the state contracts with an MCO, the state pays the MCO an annual flat fee for everyone enrolled, and then the MCO uses that money to administer the plan. In contrast to that is a fee-for-service model, in which the state pays providers on a case-by-case basis as they administer healthcare services.

As of July 2019, more than two-thirds (69%) of all Medicaid beneficiaries received their care through MCOs. How and why do managed care organizations contract with Medicaid?

It has to do with the financial model that I mentioned. Because the state doesn’t necessarily have the capacity or desire to administer every detail of its own Medicaid program, they can bring in big name, national private insurers to help them. The MCO benefits by gaining a pool of patients that guarantee a flat payment. The MCOs have a fair amount of discretion, but they must follow the terms of their contract and certain federal rules—such as providing care in the same amount, duration, and scope as the fee-for-service program. However, they are generally free to do as they like in terms of deciding the specifics of how patients receive care. They run their own provider networks, can set their own prior authorization requirements, and can impose other restrictions such as limiting which pharmacies patients get their medications from. If they run their program in a cost-effective way, they can turn a profit.

In general, can you explain how the quality of viral hepatitis care in an MCO might differ from care received through other delivery/payment models?

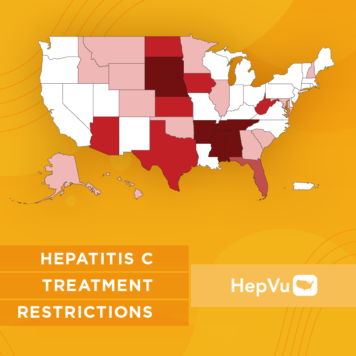

One of the challenges with MCOs is that variations between policies can lead to varying levels of quality of care within the same state. In the case of Hepatitis C, this problem is heightened, because it is still relatively common for Medicaid programs (regardless of how they are administered) to impose extreme restrictions during the prior authorization process. Depending on the nature of a restriction, some people may not ultimately be connected to care at all after receiving their diagnosis. Even small differences between the state’s fee-for-service policy versus an MCO’s policy can impact a patient’s ability to access treatment. For example, if an MCO requires more paperwork or additional test results before treatment will be approved, this can be burdensome for someone who might not have access to transportation to get to a test, or who might not have a reliable home address to receive paperwork from their MCO. Another issue with MCOs can be a lack of oversight by the state Medicaid program, because a state may have a fairly open access policy within its fee-for-service program, but the MCOs may still impose additional restrictions.

U.S. states have significant autonomy when it comes to defining and implementing their own state-level Medicaid programs. Given variations across state Medicaid programs for viral hepatitis, can you identify for our readers what elements should be present in every high-quality viral hepatitis treatment program?

I would start with open access. Removing prior authorization (i.e., the requirement that the insurer must issue formal approval before treatment for HCV can begin), a practice that many advocates have been pushing for, and that many state Medicaid programs have begun to implement. Where this is the case, patients can immediately get their prescription filled after getting diagnosed rather than having to go through the onerous process of submitting a request for treatment. Even states that feel unable to entirely remove prior authorization can remove other treatment restrictions that may still be in place, such as restrictions based on liver fibrosis or sobriety. Beyond these unfair restrictions, there are still onerous process barriers for many people at the pharmacy level. Implementing open access would mean getting rid of any restriction that isn’t rooted in the medical standard of care and making sure that people who have a Hepatitis C diagnosis are able to get the care that they need without having to go through unnecessary steps that delay or impede access to life-saving treatment.

Secondly, a high-quality viral hepatitis treatment program needs to pay attention to health equity. A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital Signs report compared different groups of people in different insurance scenarios and found that Medicaid recipients have lower odds of treatment initiation in states with treatment restrictions than in states without, and that Black people and other People of Color may have worse outcomes than white people. Any program that is looking to have the best outcomes for everyone in the program needs to keep in mind that many restrictions may have a disproportionate impact on certain groups.

One concern with managed care is that MCO’s policies can sometimes be opaque. How does this impede timely and affordable viral hepatitis care?

As advocates push to lift restrictions, it’s important to not only pay attention to fee-for-service programs, but also MCOs. Because the MCOs are private contractors who have a lot of autonomy, there is often a lack of transparency in terms of the MCO’s policies. As advocates, we may see information that a state has published on its website about a fee-for-service policy, but it may be less clear if the MCOs have implemented the same policy, because MCOs aren’t as transparent. Even in states that have lifted restrictions, there may still be MCOs doing things their own way. States need to prioritize enforcement and ensure that there is parity between their fee-for-service program and their MCOs. Additionally, it’s important for states to clearly communicate policy changes when they occur so that MCOs are put on notice that they may need to make changes, too.

How can Medicaid programs ensure quality care is given to people living with viral hepatitis via managed care models?

The most important change that Medicaid programs can make is to take away prior authorization requirements entirely, and that needs to apply to MCOs as well. States also need to ensure there is adequate oversight of MCOs and hold them accountable to providing adequate healthcare in the same amount, duration, and scope that they would be required to provide if they were part of the fee-for-service program. One way for states to ensure that MCOs don’t cause disparities in care is to carve out pharmacy benefits from the MCO contract. By “carving out” pharmacy benefits from the MCO contract, a state retains control of the pharmacy benefit and provides it to all enrollees through fee-for-service Medicaid. Some states have implemented this practice for all pharmacy benefits, while others limit the care out to specific disease states, including Hepatitis C. The real solution is to get rid of prior authorization and all treatment restrictions, but the states that don’t feel comfortable doing that should make sure the MCOs they’ve chosen to contract with are at least providing the same level of care the state would provide.