Mark Sulkowski, MD is a Professor of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

The advent of highly effective treatments for Hepatitis C represents remarkable scientific achievement marked by many important milestones including the recognition of non-A, non-B Hepatitis (1975); identification of the virus (1989); development of in vitro systems to study the virus and potential antiviral drugs (1999); the approval of the first direct acting antivirals (DAAs, 2011); the advent of the first, interferon-free oral DAA combinations (2014); and the publication of the reports from the WHO (2016) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2017) outlining strategies for the elimination of Hepatitis C in the world and United States, respectively. There is no doubt that Hepatitis C illustrates successful translational research with rapid advancement from the bench to the bedside and beyond to combat a major cause of human suffering and death.

In the United States, Ly and colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that Hepatitis C accounted for more than 19,000 deaths in 2013, which surpasses the total number of combined deaths from 60 other reportable infectious diseases, including HIV. Since the approval of DAA combination therapy in 2014, Hepatitis C treatment uptake has been relatively robust among persons with prevalent Hepatitis C infection who have more advanced liver disease and commercial or Medicare health insurance. In 2017, Goldberg and coworkers analyzed US databases, including United Network for Organ Sharing, and found a temporal correlation with a steep increase in Medicare prescriptions for Hepatitis C treatment and a decline in the number of persons listed for a liver transplant due to Hepatitis C-related liver failure. These and other observations justify efforts to identify and link older Americans with untreated, long-standing chronic Hepatitis C infection to curative and, potentially life-saving, treatment.

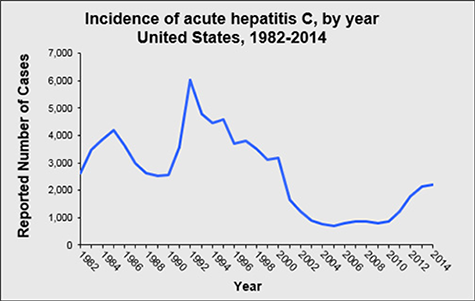

Unfortunately, in the United States, there is another side to the Hepatitis C story – one of immense, preventable human suffering due to incident Hepatitis C infection in younger individuals who are ensnared in the opioid epidemic. First, far too many teens and young adults are dying from opioid overdoses. Second, the Hepatitis C incidence is skyrocketing among young adults who inject drugs. Between 2010 and 2015, Hepatitis C infection increased by 294%, with an estimated 30,500 persons newly infected in 2014 alone.

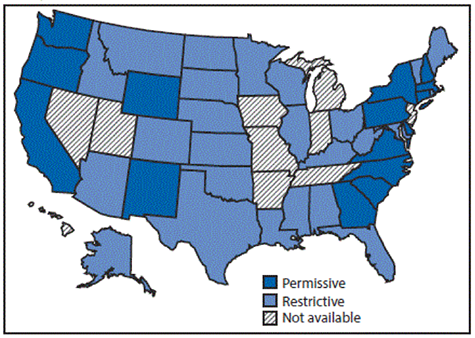

In the May 12, 2017 issue of CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), Campbell and colleagues from the CDC examined the Hepatitis C incidence and policies related to services to prevent and treat Hepatitis C for persons who inject drugs (PWID) and found that only three states had comprehensive sets of laws for preventative services and permissive Medicaid treatment policies that would allow curative Hepatitis C treatment among PWID with minimal liver disease and those who are actively using drugs.

In the same MMWR issue, Patrick and coworkers examined trends in Hepatitis C infection at the time of delivery among pregnant women from states reporting Hepatitis C on the birth certificate and found that from 2009 to 2014, the prevalence of maternal Hepatitis C infection among reporting states increased by 89%, from 1.8 to 3.4 per 1,000 live births. And this likely underestimates the actual prevalence as pregnant women are not universally screened for Hepatitis C. Importantly, active Hepatitis C infection at the time of delivery carries the potential for transmission from the mother to her child with risk estimates ranging from 3% to 6%. Curative Hepatitis C treatment of women of child-bearing potential before pregnancy would remove the risk of mother to child Hepatitis C transmission.

While these incident Hepatitis C statistics are grim and underscore the challenges to Hepatitis C elimination in the U.S., the important point is that each of these cases represents a real person adversely impacted by the virus and policies that restrict access to a Hepatitis C cure. Recently, a 24-year-old woman presented to our Viral Hepatitis Clinic for treatment of her chronic Hepatitis C infection, which was discovered after her 3-year-old daughter was diagnosed by her pediatrician after abnormal liver tests. This very difficult situation only worsened when she was repeatedly denied curative Hepatitis C treatment because her liver disease was not advanced enough. As a result, this young woman lives with the risk for liver damage and for Hepatitis C transmission to subsequent children. At this time of unprecedented scientific success and public health optimism, this is a tough pill to swallow.