Frank Hood is the Associate Director of Policy and Partnerships at the Hepatitis B Foundation and the Director of Hep B United. The following is an excerpt from his comments on HepVu’s webinar on our recent Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Status Report.

What can you tell us about your role at the Hepatitis B Foundation? What work does the Hepatitis B Foundation do to advocate for Hepatitis B-related issues in the U.S.?

I have two job titles. One is with the Hepatitis B Foundation, where I am their associate director of policy and partnerships. In that role, I oversee a lot of our state and federal advocacy around Hepatitis B as well as Hepatitis A and C. We are also focused on the syndemics of viral hepatitis, so we work not only with each other but with our HIV and STD colleagues as well.

One of the things that the Hepatitis B Foundation has realized over its history, though, is that in order to eliminate Hepatitis B, we have to tackle it from all sides. One of those sides is creating a space for those doing similar work to come together and share best practices. So, my other hat is as Director of Hep B United, which is a coalition that is co-chaired by the Hepatitis B Foundation as well as the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, also known as AAPCHO. The coalition has been around for 12 years now, and we are a coalition of coalitions, as we like to say. We are a national coalition that brings together state and local coalitions that are focused on Hepatitis B. This can be coalitions that are focused on a specific community that Hepatitis B disproportionately impacts or an organization that primarily focuses on Hepatitis B. We work to bring folks from across the country together in order to share best practices on screening, vaccination, and targeting the different areas we need to in order to eliminate this disease.

We also do a lot of capacity building. We are trying to educate on top of everything else we do, and we know that one of the key groups to educate is our policymakers. We do that through our advocacy. When we make a pitch as to why lawmakers or other stakeholders should give us more resources, we weave the message into a story. It is important to create something that hooks them, gives them the information they need, addresses why it is important, and what they can do about it all in a succinct way that holds their attention.

What is the state of Hepatitis B in the U.S., especially compared to Hepatitis C?

Firstly, we must establish where we are with Hepatitis B in the US right now. This is interesting in that Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C have the same estimated number of people living with them in the US, and some people are coinfected with both. There are 2.4 million people living with Hepatitis B in the US.

COVID-19 has also impacted Hepatitis B screening. Despite this disease having a vaccine, there was a long plateau of about a decade where we averaged between 20,000 and 22,000 new acute cases a year. Since COVID-19, however, we have seen the number of acute cases drop quite dramatically, with this trend continuing on our most recent CDC Hepatitis B surveillance report, which is in 2021.

We know that less testing was happening during the pandemic, but that also means we have now identified fewer cases which could lead to the perception that Hepatitis B is becoming less prevalent. We do not believe that is the case.

What populations are most impacted by viral hepatitis, and how does that play into the overall impact of Hepatitis B?

This is a disease that disproportionately impacts quite a few priority populations. We do have a unique scenario where many of our priority populations are based on where they were born or the racial/ethnic community with which they identify. That has long been the case, but we also now see a rising risk factor among people who use drugs, which is a behavioral category. Something that we are working to raise awareness on is that it is essential to know both who has Hepatitis B and the burden of Hepatitis B in an area. Of course, you want to treat it, but the more important thing for folks to realize is that if you do not treat it, it can lead to cancer and liver disease. Viral hepatitis is a leading cause of liver cancer worldwide.

Identifying and vaccinating against Hepatitis B or ensuring people who have Hepatitis B are treated then prevents someone from progressing to liver cancer or from spreading the disease. Treatment is prevention. People do not understand that Hepatitis B then leads to liver cancer and sometimes death. Liver cancer rates have only recently started to decline, but we still need to do more to raise public awareness around this. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and others have recently made changes to their screening regulations and their vaccine guidelines to try to continue this progress.

What role does robust viral hepatitis surveillance play in preventing and treating Hepatitis B?

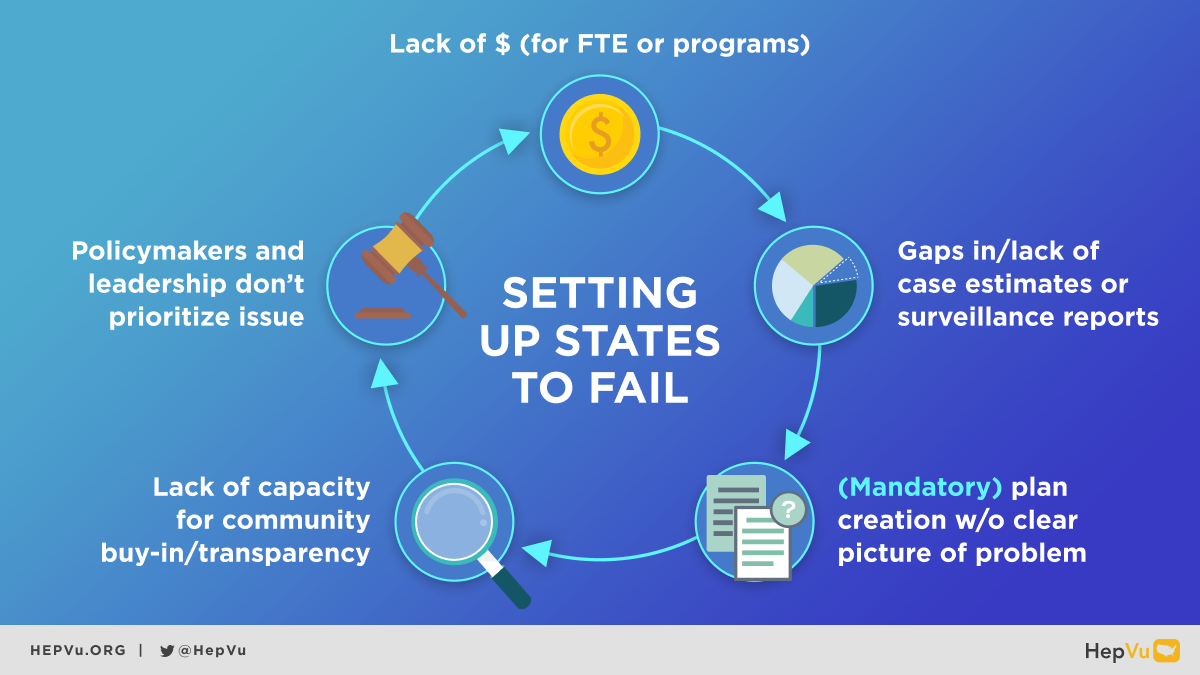

If we take this surveillance status report and pull out themes from it, one really stood out to me. The public health infrastructure sets states up to fail. States are under-resourced, and I was told by those who have been here much longer than I have that it has been a chronic issue. Not only regarding public health overall, but hepatitis is chronically underfunded, and that results in fewer people and fewer programs those people can do. There is, overall, just a lack of money.

As this report shows, we have states that leave gaps either in case estimates or are not producing surveillance reports. Tests might be coming in, but they are not getting assessed or analyzed. When we look at which states are doing this analysis versus which ones are not, it is very clear that the ones that do not have a full-time employee dedicated to surveillance are the ones who are not able to do it, which is clearly a capacity issue. All of these states are getting funded, but they might not have a full-time employee. These states must make a plan in order to receive this funding, but they are now creating this plan without a crystal-clear picture of what the problem is because they have not had the capacity, ability, or resources to go and produce the surveillance reports or to analyze the data.

The folks doing this work are trying their best, but if they have the jobs of three people to do and only half the time to do it, some things will not be the way we would like or be as good as we would like. Without a publicly available plan with community buy-in, it is an uphill battle to advocate for funding from policymakers and leaders. It is a vicious cycle.

What is the importance of having full-time employees (FTEs) dedicated to viral hepatitis surveillance, and how many are needed?

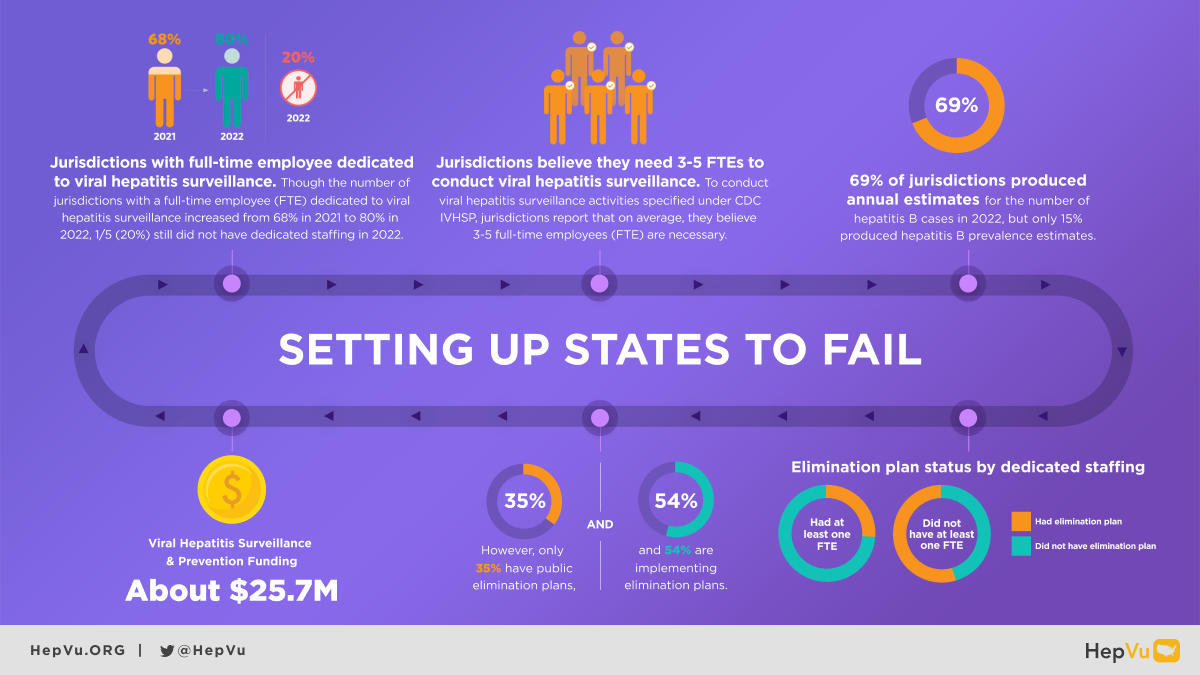

The jurisdictions that have full-time employees are able to do surveillance reports in a way that those without do not. According to HepVu and NASTAD’s newest Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Status Report—which assesses the status of viral hepatitis surveillance practices across U.S. jurisdictions in 2022—jurisdictions have stated that they need three to five full-time employees to truly do the surveillance activities that they are being asked to do.

As I said, those who have had an elimination plan have been able to do it because they have had dedicated staffing to be able to do it up to this point. However, only a third of the states have a public plan. As someone who has worked on several states’ plans, particularly in the last eight years, any plan the federal government has tried to implement has not gone well. There is a lack of transparency and community buy-in around these federal proposals, and we would rather it be a place where everyone feels good about the plan, and we can get buy-in. It does show us in an advocacy sense that we are asking our states to do something that they are not resourced to do, and that needs to change.

I do not think it is the folks who are doing that job who are at fault. I think they are doing their best. It is the fault of those supplying them with the resources and capacity to do it, who are usually policymakers, which is why we need advocacy. That is the ugly cycle we are in. I am thrilled about the more specific data around Hepatitis B and C, but it really does scare me that so many states cannot do some of these activities. As we saw with COVID-19 especially, some of the most basic and essential aspects of public health are missing, like contact tracing, follow-up, and the ability to create prevalence estimates year-over-year. This report by HepVu and NASTAD does a great job of shedding light on where we are, but it is sad to see how much work still needs to be done.