Lesley Miller, MD is a Professor in Emory University School of Medicine’s Division of General Internal Medicine and the Medical Director of the Grady Liver Clinic at Grady Memorial Hospital.

Q: Your career includes extensive clinical experience, research, and teaching on Hepatitis C, especially among underserved populations. How did you get involved in this work?

I got involved in this work when I started working at the Grady Liver Clinic in 2004. The Liver Clinic is a primary care-based Hepatitis C clinic at Grady Memorial Hospital, a safety net hospital serving medically underserved people in Atlanta. The clinic was started when a colleague noted the high prevalence of Hepatitis C at Grady, yet no designated clinic to care for patients living with Hepatitis C. It’s a really important place that provides access to Hepatitis C treatment for those who would otherwise lack this access.

I’m a general internist, a primary care provider. The unique thing about the Liver Clinic, especially when it started, is that it’s housed in our Primary Care Center and staffed by general internists. General internists have a great skill set to manage Hepatitis C because we can also educate, counsel, and manage co-morbidities.

The beauty of treating Hepatitis C as a general internist is that instead of chronic medical problems that we commonly manage like diabetes and hypertension, Hepatitis C is a disease that can be cured. To be able to tell a patient that yes, you have lived with this for a long time, but now you can move on and deal with other things is a powerful and awesome opportunity.

My colleagues are also a huge plus of working at the clinic. There are six general internists in my division who all work at the Liver Clinic and we have been able to train generations of providers to do Hepatitis C treatment. These folks are super committed to both treating the disease and the patients living with Hepatitis C.

Q: As Medical Director of the Grady Liver Clinic, what are the treatment restriction challenges that you and other medical professionals face when providing Hepatitis C care to patients? What strategies have you used to overcome these challenges?

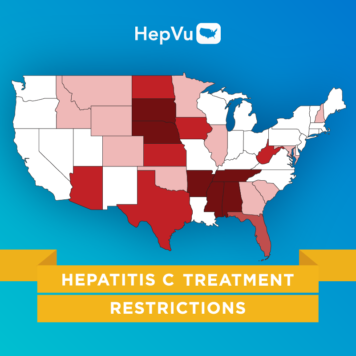

We’re definitely in a better place now than when direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) were introduced in 2014. However, we still face some restrictions in three major categories: fibrosis (liver scarring), sobriety, and provider type.

Regarding fibrosis restrictions, it was a huge deal when the new DAAs first came out because the guidelines in Georgia (both Medicaid and private payers) stated that providers could only treat folks with advanced fibrosis (liver damage) — for patients with less advanced fibrosis, we needed to wait before treating them. We were telling people that we know you have this chronic disease that’s curable, but you have to wait until you get sicker, which was really challenging.

We had several conversations with representatives and during those discussions, we broke down the fibrosis restrictions barriers using evidence-based, national guidelines on hcvguidelines.org, a collaborative project from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), that indicated people with Hepatitis C should be treated regardless of their fibrosis. It’s difficult to argue with evidence and those guidelines became our most powerful tool.

We still wrestle with sobriety restrictions, which require a period of abstinence from drugs and/or alcohol before treatment can begin. Again, the national guidelines do not support lack of sobriety as a reason to restrict treatment. We always go back to the guidelines again and say, “This is not an evidence-based reason to restrict Hepatitis C treatment and it’s not in line with national guidelines.” It’s also important to convey that message to patients. When I see a patient who may have active substance use, I say, “Your insurance company may put up barriers around this, but I want to reassure you that I’m committed to helping you overcome them and start your treatment.” I let patients know that our team will present evidence from the guidelines to their payer and continue to appeal to get them access to treatment.

For provider restrictions, it’s especially relevant in our clinic because we are general internists and insurance companies might say Hepatitis C treatment needs to be done by a specialist in gastroenterology, hepatology, or infectious diseases. At Grady, our generalist treatment model works well, and we’ve been at the cutting edge of providing new treatments, sometimes even before other specialty clinics. We treat close to 500 patients a year and have been doing it for years, so I accurately describe my provider specialty as “Internal Medicine/Hepatitis C” and that has worked well. Also, there is often an option for a non-specialist to treat “in consultation with” a specialist, and fortunately, we can turn to our gracious hepatology colleagues at Emory Healthcare if the need arises.

One thing that has been helpful in our clinic is that our healthcare system provides resources around Hepatitis C treatment by appropriately leveraging the 340B program. The 340B program allows certain providers, such as safety-net hospitals, to stretch federal resources to reach more patients and provide comprehensive services. Once we really ramped up our treatment after the introduction of DAAs, Grady used the 340B program to make an investment of staff resources into our clinic that created multiple new positions. These included a patient navigator, nurse practitioner, clinical pharmacist, program manager, and a medication access coordinator position, which was important for treatment access. The coordinator is a pharmacy technician who is responsible for prior authorizations and patient assistance program applications, which is so helpful in overcoming some of these treatment restriction barriers. I know not every clinic has the resources to have a full-time person in this role, but specialty pharmacies can also play that role and help address the barriers to start treatment.

Q: Based on your experience in Atlanta, how do social determinants of health play a role in restricting access to Hepatitis C diagnostic and treatment services, especially among medically underserved populations?

Social determinants of health are a huge issue because they create many competing health priorities. Hepatitis C treatment can also be expensive. Since we don’t have Medicaid expansion in Georgia, there are many uninsured patients and many of them aren’t able to afford care in traditional specialty practices. Through the Grady Liver Clinic, we’re able to increase access to Hepatitis C care for these patients. Uninsured patients in our catchment area can access care regardless of their ability to pay.

In addition, at the Liver Clinic, we have resources and staff to help patients navigate these competing health problems and cost concerns. In addition to the staff I mentioned above who all work as a team to support patients through workup and treatment, we also have social workers and our faculty clinicians. Grady has been very proactive about addressing these social determinants of health to ensure that people living with Hepatitis C can access the care they need. But I’m also very conscious of folks outside of our catchment area, in the more rural areas of the state, who don’t have this access. We try to share our model and do trainings for other providers throughout Georgia as much as we can so people who can’t access our services directly can also benefit from what we’ve learned over the years.

Q: You have advocated for improving treatment access, including new outreach approaches for marginalized populations. Can you expand on these approaches and how they can improve Hepatitis C treatment and care?

Our model has been successful, so we’re trying to replicate our efforts by working with health systems treating populations similar to ours, where access to care and treatment is an issue. Even people who are eligible for care at Grady may have barriers in coming to our clinic, so I do a lot of trainings for other healthcare professionals so they can start their own treatment programs and meet their clients where they are. It’s like teaching folks to fish by providing knowledge and skills and also spreading the word about how awesome and fulfilling it is to treat and cure Hepatitis C, which is really appealing to general internists who often deal with chronic conditions. I’m super enthusiastic about hyping up Hepatitis C treatment to other primary care providers. Being able to treat this disease and cure so many people is the best thing that has happened to me in my career. I try to spread my excitement to other primary care providers to let them know that if we can do this in our clinic, they can do it, too.

My colleagues and I have done workshops and trainings for family medicine providers at their national meetings, for the Society for General Internal Medicine, and even held our second annual “Hands on Hep C” symposium last month, aimed at training non-specialist providers in Georgia to treat Hepatitis C. We gave them a practical toolkit on Hepatitis C screening and treatment to let people know that it’s absolutely feasible to treat Hepatitis C as a general internist, a family practice provider, a non-physician practitioner, or a provider who treats people with substance use disorder.

For people with substance use disorder, it can be difficult to access treatment, so bringing the care to them is more patient-friendly and realistic. To that end, I’ve done trainings at local substance use disorder treatment clinics to educate providers on how to screen and provide treatment onsite. All it takes is one person to catch that spark and want to treat Hepatitis C and they become the local expert. Down the line, someone else catches that spark and the care expands.

An exciting venture we just started is our own viral hepatitis Extension for Community Health Outcomes (ECHO) partnership with the Georgia Department of Public Health. We just kicked off our first monthly session in April and we hope to reach folks around the state to bring us cases for discussion and build that workforce to treat Hepatitis C. Each session has a short 20 minute didactic by a viral hepatitis expert and then the participants from all over the state bring their de-identified patient cases to the group to discuss general workup and treatment strategies, serving as a knowledge network. Ideally, everyone learns and folks build their confidence as providers when they’re first starting out by having experienced providers offer guidance and support.

Q: As a clinician, how would you suggest the provider community and other stakeholders in the viral hepatitis space work toward eliminating Hepatitis C treatment restrictions in the U.S.?

For me, it always comes back to the patient. My patients are the motivation behind my work in Hepatitis C. Sit down with your patients and listen to their stories to see the barriers they’re facing. Doing that day after day continually reinforces my resolve to get folks better care and break down these treatment barriers.

Get informed about the treatment restrictions through resources such as the State of Hepatitis C report from the National Viral Hepatitis Round Table (NVHR) and the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI). Knowing what’s out there and what you’re up against is first. Second, get involved in advocacy organizations such as NVHR, which I’ve been a part of for many years; they’re great at disseminating information and opportunities.

Third, networking with other providers is helpful to understand how people are providing care across the U.S. and is very useful in creating inclusive solutions. Finally, interact directly with policymakers. I went to the Georgia state capitol and talked about Hepatitis C to educate the policymakers with the clinical and epidemiological knowledge they need. There are many ways to get involved in this space and if you’re seeing patients with Hepatitis C, it becomes a natural motivation because you want to fight to easily treat and cure your patients.