Dr. Jagpreet Chhatwal is an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and director of the Institute for Technology Assessment (ITA) at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Much of your work has focused on the health economics of Hepatitis C and other liver diseases. What drew you to this line of research?

In 2013, when oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for Hepatitis C treatment got approved by the FDA, there was a lot of discussion about the price of drugs, which could cost payers as much as $84,000 for the entire course of treatment. A lot of attention was paid to these drugs because they were essentially a cure for Hepatitis C, which had never existed before. 95% of people who were taking DAAs for Hepatitis C were cured. But price was the concern—was the cost of curing Hepatitis C worth it?

At that time, we got involved in a project looking at the cost effectiveness of Hepatitis C treatment. We published a study showing that this treatment is highly effective and highly cost effective despite the high price tag. But the problem remained that despite the high level of cost-effectiveness, the treatment course was unaffordable for most insurance payers due to the large number of people who needed treatment. The millions of people that needed to be treated in the United States was too large for any single payer to afford.

A lot has changed since the launch of DAAs. The prices of DAAs have come down, and there a lot of discussion about how we can scale up HCV treatment. But because the budget needed to treat all of those infected is still substantial, many payers added restrictions on who can get treated and who can provide these curative treatments. A meta-analysis by our team showed that HCV treatment at current price is now cost saving—HCV treatment not only saves lives but saves cost.

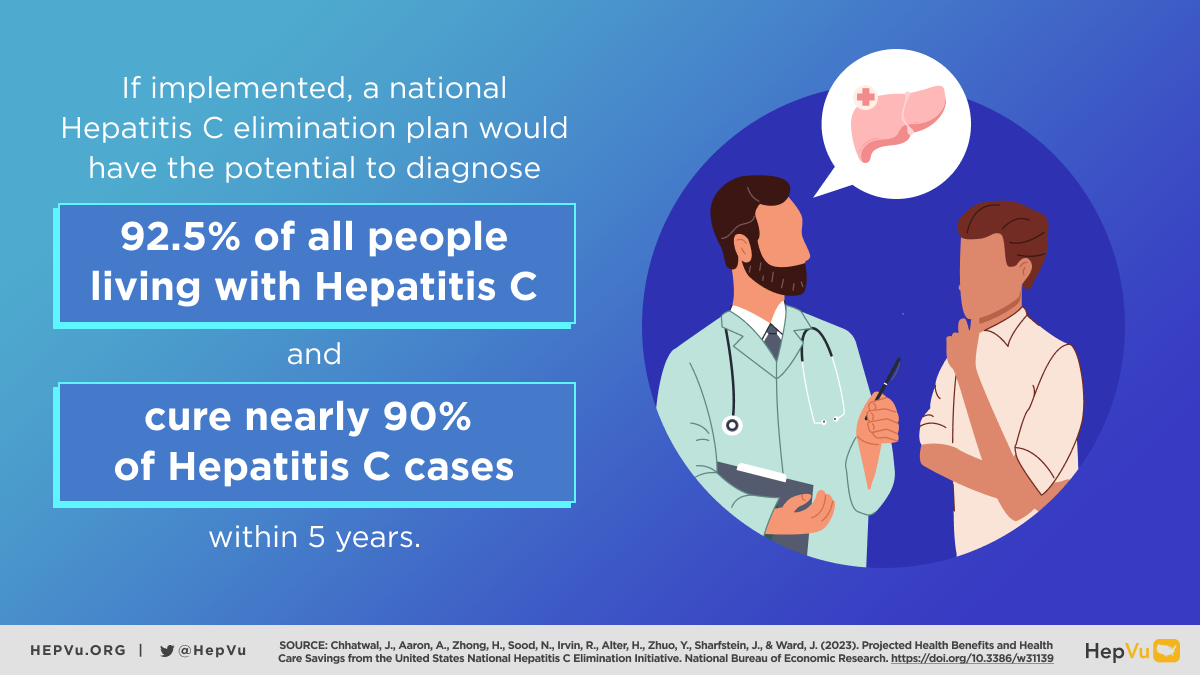

Your recent paper “Projected Health Benefits and Health Care Savings from the United States National Hepatitis C Elimination Initiative” estimated that the White House’s proposed Hepatitis C elimination initiative would, if implemented, diagnose 92.5% of all persons with Hepatitis C and cure 89.6% of Hepatitis C infection within five years and avert over 24,000 deaths. What factors in the planned initiative led you to these conclusions?

In 2020, there were some changes in screening guidelines. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated Hepatitis C screening guidelines to implement universal screening, since almost 50% of people living with Hepatitis C do not know that they have it. Then, last year, the White House proposed this national initiative to eliminate Hepatitis C, and our objective was to evaluate this plan’s potential benefits. The analysis you’ve cited focused on the clinical benefits as well as the cost implications and the potential cost savings.

Using a mathematical model, we evaluated what could happen in the long run if we implement such an initiative. The initiative’s plan boils down to two strategies: to scale up treatment and reduce any barriers to treatment. Our projections suggest that the U.S. could administer DAAs to up to 300,000 people each year under the proposed initiative.

How is that compared to the current standard of care? Right now, we are treating approximately 84,000 people each year. In order to achieve Hepatitis C elimination, we really need to scale up treatment, which also requires increasing awareness of the disease, identifying people who are unaware of the disease, and making them aware of their status through easily accessible testing and linkage into care.

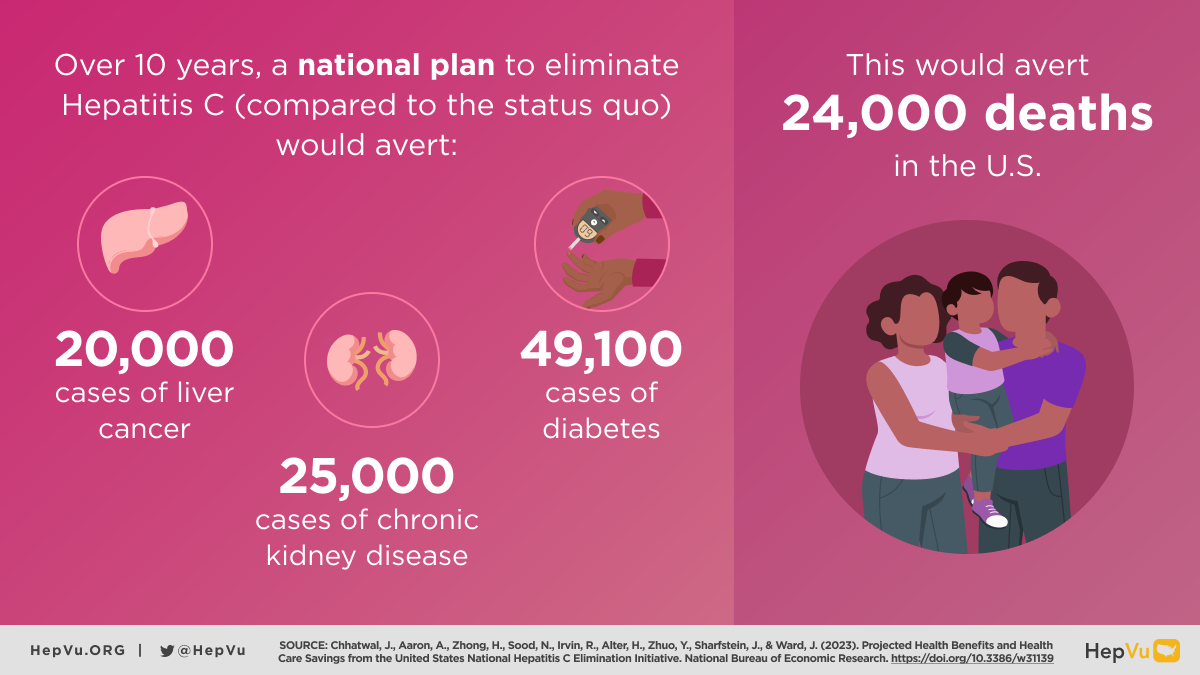

We know that Hepatitis C, if untreated, can lead to liver disease, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and then death. By scaling up treatment efforts, our model shows that the U.S. could increase the number of people who are being treated and prevent new infections that would otherwise lead to liver cancer or end-stage liver disease, averting close to 24,000 deaths in the next decade.

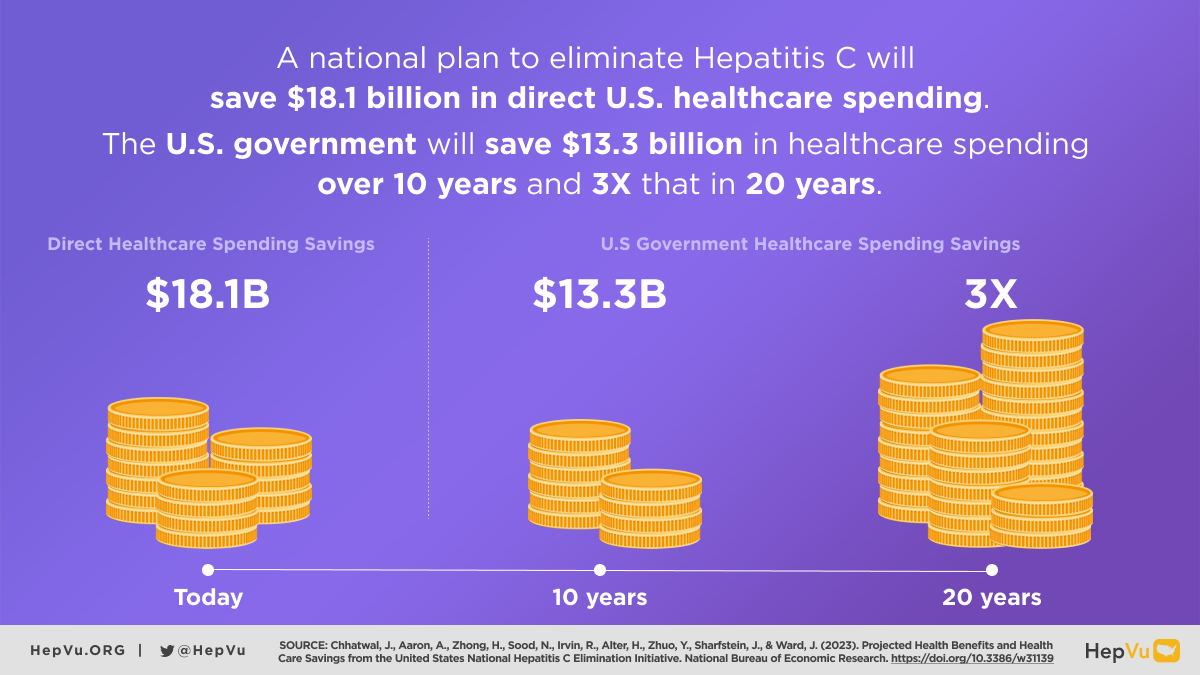

You and your coauthors predict that the federal government would save over $13 billion in healthcare costs within 10 years, with that number potentially doubling over 20 years. What is the benefit of framing healthcare initiatives like this one in terms of cost savings?

Such an initiative requires initial investment to scale up screening and scale up treatment. That means there is a need to invest in resources for those programs, but once we invest those resources, the expectation is that these downstream savings will accrue by ultimately averting new liver cancer cases and the need for liver transplants. Which by the way, is almost half a million dollars per transplant. Also, in addition to these liver-related conditions, we could avert many new cases of diabetes and chronic kidney disease since both of these conditions occur more frequently among persons with hepatitis C infection.

By avoiding all these downstream adverse outcomes of Hepatitis C, we’re also saving the resources that would’ve gone into managing those conditions. All told, these savings could be as large as $13 billion for the federal government itself alone over the course of the initiative.

This is important because it gives the government an incentive to invest in the initial resources needed to launch this national initiative.

The political environment for budget increases is particularly challenging right now. Why is it important to implement a national Hepatitis C elimination plan regardless of these political headwinds?

What we are trying to emphasize here is that this plan is so unique in that it does not only save lives: it also saves resources. That is important irrespective of the political situation and irrespective of the budget constraints. We can achieve cost savings if we are able to implement this plan. It is not just saving lives; it is also saving the dollars we are going to have to spend anyway on chronically infected persons who haven’t been cured of their hepatitis C. So, we feel that this is an important message that cuts across politics and hopefully gets the attention that this plan needs and deserves.

According to your paper, Hepatitis C “disproportionately affects certain marginalized and/or minoritized communities, including those who are uninsured, American Indian and Alaska Native persons, non-Hispanic Black persons, incarcerated populations, and people who inject drugs who often have less access to medical care.” In your opinion, how do we ensure that large national initiatives like the one the White House has proposed are carried out in an equitable way, and reach the marginalized populations who are most at risk?

What the White House plan will provide is the resources that are needed in different settings, sectors, and jurisdictions to scale up the treatment and screening that is needed in marginalized populations. One of the reasons why marginalized populations have high prevalence is that the resources are limited in those settings and diagnostic and treatment services are much harder to access. We know that the epidemic is being driven, in part, by these health inequities. Individuals who inject drugs, for instance, are particularly impacted by Hepatitis C, and are frequently unable to access client-centered, community-based testing and treatment services. The benefit of a national plan is it will have the ability to work towards elimination in many ways at once.

Providing more resources through this initiative will address the limitations of the current status quo. We believe that by utilizing those resources in different jurisdictions, and employing different models of testing and treatment, we can reach those marginalized populations and see the full impact of this initiative.