Eric Hall, PhD, MPH, is a Postdoctoral Researcher for the Department of Epidemiology at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health.

Q: Your research focuses on county-level overdose mortality and opioid prescription rates. Can you explain what these rates mean and how they relate to the viral hepatitis epidemic in the U.S.?

Over the past few decades, the opioid epidemic in the U.S. has caused several important public health consequences. The most noteworthy is the significant increase in drug overdose deaths, which has largely been driven by an increase in deaths due to opioid misuse. Since 1999, nearly half a million people have died from an opioid-related overdose. In this research, we were interested in how drug overdose deaths relate to opioid prescribing practices in different parts of the country. We used two main sources of data to answer this question. First, we used data on overdose deaths, which are collected from death certificates indicating drug poisoning or overdose as a cause of death. Second, we used Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s data on the number of opioid prescriptions per person. These data come from a system that monitors pharmacies’ prescribing practices.

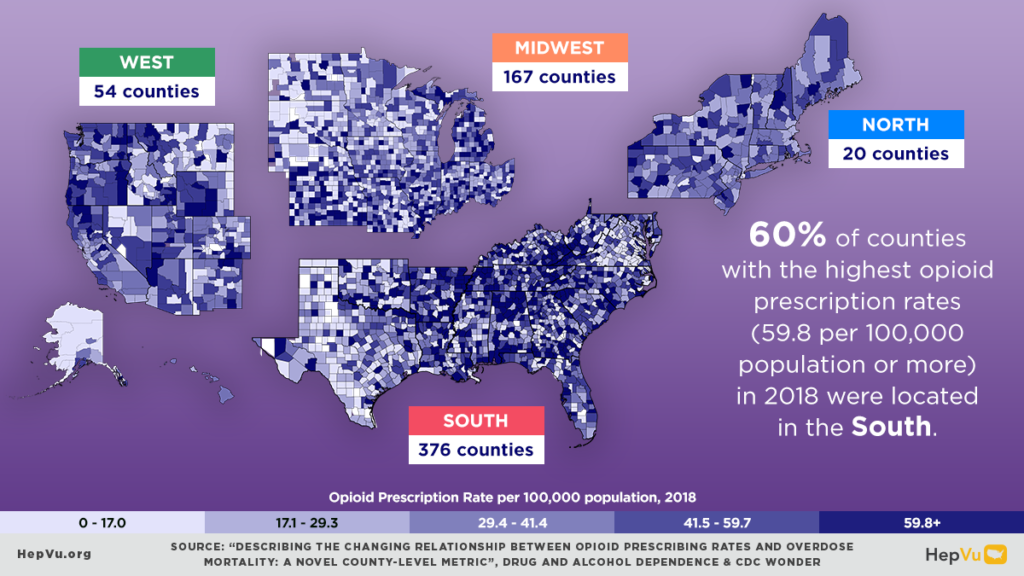

Prior to doing this analysis, we knew that some of the increase in overdose mortality was attributable to over-prescription of opioids, but we didn’t know how the relationship between overdose death and prescribing practices differed by time or geography. As a little bit of background on this – over-prescription of opioids in the U.S. was driven by pharmaceutical marketing efforts and clinical practice changes in the nineties, specifically practices for managing chronic pain. In response, the public health community started to implement different measures to reduce the over-prescription of opioids. In fact, the national rate of opioid prescriptions has decreased since 2012. Despite this decrease, the national rate of overdose deaths has continued to increase, indicating a shift away from prescription opioids to illicit opioids and other drug types that are more likely to be injected. This shift to increasing injection drug use has led to increased infectious disease transmission, including an increase in new cases of Hepatitis C.

Q: Can you describe the key findings from your recent study, “Describing the Changing Relationship between Opioid Prescribing Rates and Overdose Mortality: A Novel County-Level Metric,” published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence? What kinds of data are important for helping us to understand geographically specific changes in the relationship between opioid prescribing practices and overdose mortality? Where are data still lacking?

On a national level, the relationship between opioid prescribing practices and overdose mortality rates remained relatively steady from about 2006 to 2011. But since 2012, the number of overdose deaths per 100,000 opioid prescriptions has increased — reinforcing our knowledge on the shift from prescription opioids to illicit opioids and other drugs. We found that the degree of this shift differs by regional characteristics. Investigating some of those characteristics provided additional insight into the interaction between prescription opioid availability and drug overdose mortality. We investigated a variety of social determinants of health that we thought might impact both the availability of opioid prescriptions and overdose deaths. Some of these social determinants of health included the primary economic industry, gross domestic product, education, income, poverty, and food insecurity. From this analysis, we found that wealthier counties or counties with higher levels of education and life expectancy have experienced a sharper increase in the number of overdose deaths per opioid prescription, meaning overdose deaths in those counties are increasingly less likely to be caused by prescribed opioids.

We need more data to understand why the relationship between overdose deaths and opioid prescriptions varies by geography and characteristics of populations. For example, data on county-level policies that aim to reduce opioid prescribing practices or reduce overdose mortality are key to understanding the relationship between opioid prescribing practices and overdose mortality.

We also lack data on the availability of different drugs – both prescription opioids and other drugs – in different places. This is important because some drugs are much more deadly than others. Some of these data are collected through toxicology reports, medical examiners, coroners, law enforcement, and crime labs, but we need a more coordinated and timely approach to fully understand how geographically specific drug availability (both licit and illicit) may affect overdose mortality.

Q: When looking at trends in overdose mortality, the article noted a shift away from prescription opioids to other drugs. What are these other drugs and in what regions of the country is this shift away from prescription opioids most pronounced?

Although we didn’t study that in this paper, other previous analyses of toxicology reports from death record data show a recent increase in overdose deaths involving synthetic and illicit opioids, such as illicitly manufactured fentanyl. Recently, there’s also been an increase in deaths involving stimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine. In this paper, we didn’t specifically look at regional differences between those types of drugs, but previous research has indicated that increases in overdose mortality involving illicit opioids and/or cocaine have been highest in the Northeast, while increases in mortality involving methamphetamines have been highest in the West.

Q: The paper calls for more innovative and multi-sectorial overdose surveillance systems and recommends using the study’s metric to assess the impact of policies and interventions on overdose mortality rates among various regions. Why are these surveillance systems necessary and why is it important to use county-level data whenever possible?

In general, comprehensive and systematic surveillance systems ensure that data are collected in a standardized manner that allows comparisons over time and across different jurisdictions. In this case, county-level data is particularly important because national data may fail to show differences and changes occurring at smaller geographic levels, like counties. Additionally, many public health programs are implemented at the county level – having county-level data can help create interventions that are specific to that county’s needs.

It’s important to note that the availability and use of different drugs can change quickly, which makes monitoring the drug overdose epidemic particularly challenging. Therefore, we need to turn to different innovative data sources, such as data from emergency room visits and law enforcement agencies, that can help provide a more holistic understanding of the overdose mortality epidemic.

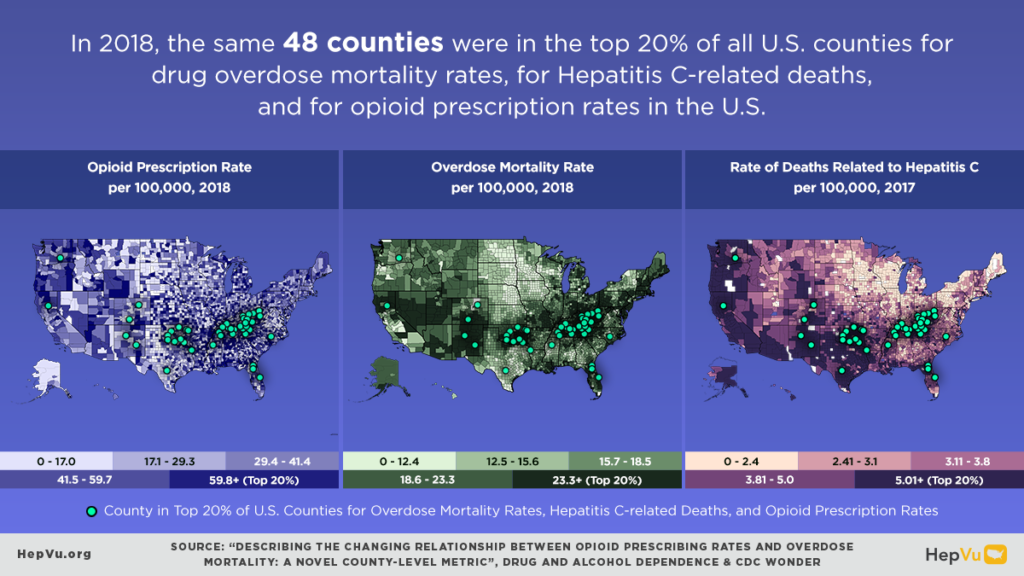

Q: How can we utilize the existing county-level Hepatitis C-related mortality data and maps on HepVu and the new county-level opioid prescribing rates and overdose mortality maps to better understand the viral hepatitis landscape across the country?

These new county-level data points and maps are pieces of the larger viral hepatitis picture that provide insights into the geographic differences across the U.S. The county-level Hepatitis C-related mortality data released earlier in the year visualizes where people are currently infected with and dying from Hepatitis C. The new opioid prescribing and overdose mortality maps can be used to inform strategies that aim to reduce Hepatitis C-related transmission and mortality, such as providing access to harm reduction services, including syringe service programs, and increasing opportunities for Hepatitis C diagnosis and treatment. In addition, the maps can help identify areas experiencing an increase in injection drug use and the subsequent increases in Hepatitis C transmission. Ultimately, these maps and data can be used together to help identify areas that would benefit from programs or interventions that aim to prevent Hepatitis C transmission and reduce overall drug overdose mortality.